In the previous part of the Manila report, we explored several well-known areas: Makati and Intramuros. These districts serve as the city’s business and historical centers. However, according to local experts, this is still not the real Manila. Just across the Pasig River from Intramuros lies the district of Quiapo. You can reach it by light rail, and the station carries the same name. That is exactly what I did. I got off the train, walked downstairs, and suddenly found myself in a completely different world.

At once, I plunged into a noisy, dirty, highly contrasting, and very chaotic city. It felt intensely oriental in spirit. Almost immediately, people began to stare at me. Apparently, few tourists come here. In response, I started taking photos of everything around me. I captured a sleeping girl on a cart, children digging through piles of garbage, motorcyclists who seemed ready to run me over, and men casually massaging each other. Around them stood vendors selling absolutely everything, from keys and signs to strange and unknown trinkets.

I knew that the Church of Quiapo, also called the Basilica of the Black Nazarene, stood somewhere in this district. Instead of following the main streets, I chose to cut through narrow alleys. As it turned out, this decision led me to the most interesting part of the area. I found myself in what felt like one enormous market. Although the official market occupies a central section of the district, the surrounding streets differ little in terms of crowd density and the number of stalls. The scene looks extremely colorful. Here, people sell everything from gold and diamonds to live chickens and exotic fruit.

Some locals looked at me with suspicion.

Others, by contrast, smiled and happily posed for photos.

After wandering through this lively display of local trade, I checked my phone and realized how far I had drifted from my route to the church. As a result, I had to walk back through the same maze of sellers, bicycles, carts, motorcycles, and even jeepneys squeezing through the crowds. In one courtyard, for reasons I still cannot explain, I noticed a Christmas nativity scene. It was not for sale. It simply stood there, which felt perfectly normal, since it was still January. Eventually, I reached the square in front of the basilica. There, I saw a dense crowd, a long line to see Jesus, groups of beggars and disabled people, and vendors offering questionable souvenirs and everyday goods.

So, the Church of Quiapo, officially known as the Basilica of the Black Nazarene. Builders originally completed it in 1574. As often happens in the Philippines, fires, wars, and earthquakes repeatedly destroyed the structure. The main part of the present building dates back to 1889. After a major fire in 1928, the church underwent another restoration, though less drastic. Later, in 1984, it expanded further. Finally, in 1988, the Catholic Church granted Quiapo the status of a Minor Basilica.

Today, however, the church is famous mainly for its statue of the Black Jesus. An anonymous Mexican sculptor created the statue in 1606, and a galleon later brought it to the Philippines in the mid-17th century. The dark color of the figure has several explanations. Some people blame candle soot, others point to a fire aboard the ship, while another theory focuses on the material itself, mesquite wood. Opinions differ. As you might expect, the original sculpture did not survive. During the liberation of Manila in 1945, it was destroyed. What visitors see today is a replica made from photographs, although the original head remains preserved.

As I soon realized, I had arrived during a religious event. The statue of the Black Jesus was accessible, and a long line had formed. I joined it. Women brought necklaces woven from tropical flowers, and I followed the example of local Catholics. I touched the hand of Jesus of Nazareth and made a quiet wish. At least, I think I did. Soon after, I moved on.

Next, I planned to visit the only metal cathedral in the Philippines. According to some sources, it is also the largest metal church in the world. Other sources even claim that Gustave Eiffel contributed to the design, although Genaro Palacios served as the main architect. On the way, I passed aging jeepneys, a playground built from concrete and metal, and a lively basketball game. Eventually, I reached my destination.

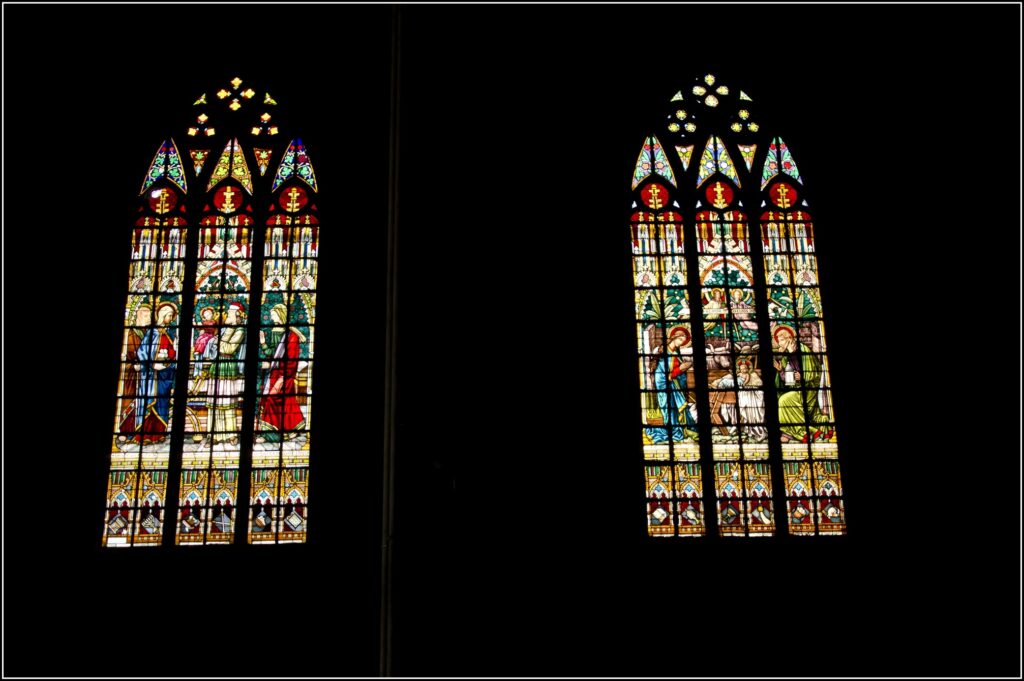

The cathedral officially bears the name Basilica of Saint Sebastian. In 1890, Pope Leo XIII personally granted it the status of a Minor Basilica, just one year before construction ended. Metal dominates both the exterior and the interior. To me, only the benches seemed free of it. Workers produced the metal blocks in Belgium and shipped them by sea together with the craftsmen. These specialists were so impressed by the idea that they came to witness the laying of the foundation stone. Meanwhile, German workshops created the stained-glass windows. Without doubt, this cathedral ranks as a must-see sight in Manila. I cannot recall another building quite like it anywhere else in the world.

It was time to leave the temple and check the map. To my surprise, Malacañang Palace appeared to be quite close. After all, this is the presidential palace. I could not miss it, so I started walking toward the Pasig River. Along the way, I passed a fire station, roosters, Filipino schoolgirls, and some kind of monument.

On the map, the route looked much shorter than it felt in reality. Moreover, the map ignored the +30°C heat and the strong sun, even though it was already four in the afternoon and the temperature should have been dropping. Soon, I realized that the walk would take longer than expected. Because of that, I stopped at a street vendor to refuel with a fruit-and-milk shake. While I waited in line, several young Filipino students showed up and began practicing their English with me. They had apparently graduated from school just the day before.

When they learned that I was heading to the palace, they immediately tried to talk me out of it. According to them, you need to book a tour almost two weeks in advance. In addition, checkpoints prevent visitors from getting close, and most people only see the palace from the river. Then they added, “Let us show you how we have fun in Manila — with cigarettes.” For a moment, I imagined something much stronger. Instead, they handed me a candy. It turned out to be a simple lollipop. “Put it in your mouth and smoke a regular cigarette,” they said. I did exactly that. “And?” I asked. “Doesn’t the cigarette taste like fruit?” they replied proudly. Naive Filipino students. When we were your age… Still, it felt strange to remember that in this same country today, people suspected of drug involvement can be shot without trial.

In the end, I had no time to visit the palace. I needed to reach the Northern Cemetery, and evening was approaching. Walking among graves in the dark did not sound appealing. Therefore, I headed north by jeepney. Fortunately, the third driver I asked was going in the right direction. I felt even luckier when guards initially refused to let me in, mentioning security rules and a 6 p.m. closing time. However, I managed to convince them that I would not stay long. That was how I learned that people actually live in the cemetery. It even has a security post, just like any residential complex.

I did not stay for long. I walked around until darkness fully set in, took a few photos, avoided being robbed, and even shared a drink with local alcoholics. Some offers are simply impossible to refuse. The Northern Cemetery feels like a city within a city. Life there runs calmly and in an organized way. I would recommend it as one of Manila’s main attractions for travelers who enjoy unusual places.

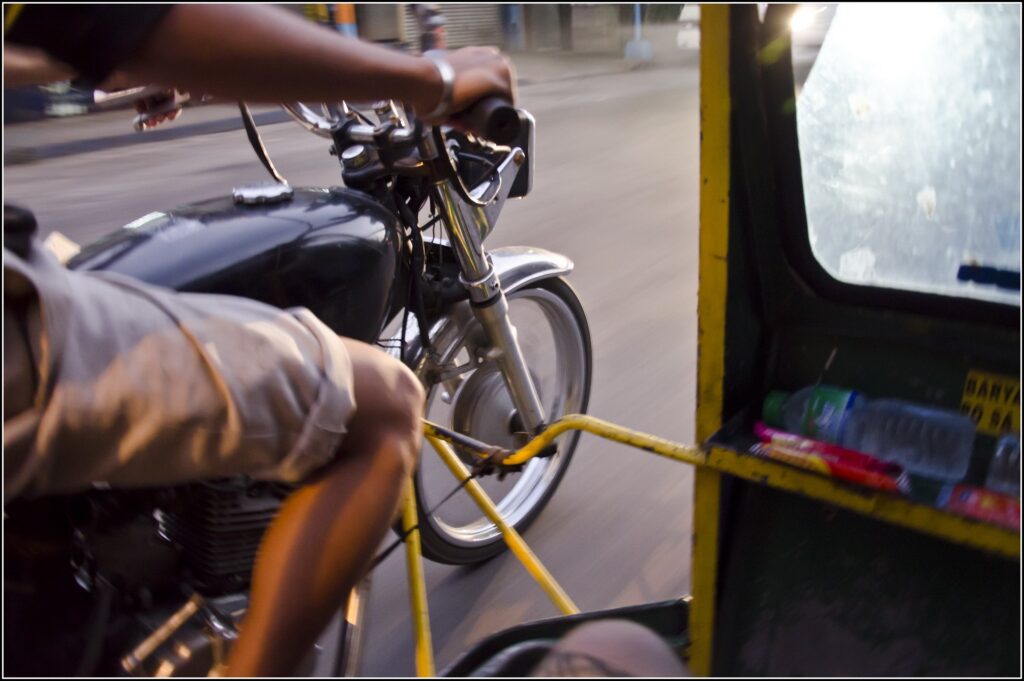

That marked the end of my intense journey through Manila. Next came a meeting in Makati, in a respectable bar. To get there, I took a train similar to the light rail I had used earlier. As a final highlight, I reached the station from the cemetery on a type of transport I had never tried before — a motorbike with a sidecar.